Across time and history, human beings have striven to understand and shape the world around us so that we might improve the quality of our lives: advancements in medicine for more years, specialized homes and furniture for safety and comfort, vehicles for taking the load from our feet and backs and granting us faster travel than we could ever hope for with our own bodies. Over the millions of years of our existence we have crafted tools to help us realize these visions and aid us in the development of technology. Indeed, tools themselves are a manifestation of these visions – technologies specifically designed to carry out functions we would otherwise be incapable of. In the grand scheme of things, every tool has played some role in making a new process possible. Yet, of all such devices past or present, only the lathe is known as a mother of tools.

Lathes are machining tools that rotate material around an axis so that other tools may cut it into a desired shape. The oldest known use of the lathe dates to the thirteenth century BC, in which ancient Egyptians woodworkers are believed to have developed some of the first versions of its kind. With a length of strap wrapped around a spindle, one operator pulled each end back and forth to create rotary motion while another held a cutting tool to carve the surface away from the spinning material. In time, other civilizations learned to build these early lathes, and over the next few centuries the Syrians, Greeks, and Romans adopted the technology. The Romans would eventually redesign the lathe so that a single person could operate it. While the bow-driven lathe could operate without a pair, it did so at the cost of accuracy and rotary strength, as it required the operator to split the machine’s function between both hands.

As the Roman Empire fell and gave way to the Middle Ages, the lathe survived, and while it’s hard to determine the exact date, historians believe it to have been modified again in the centuries leading to 1300 AD. This new lathe made use of a pole’s springy action along with a foot pedal to pull the spindle cord. With this new advancement, a single turner could operate the device without the loss of accuracy inherent to its predecessor.

Some of the earliest illustrations of this evolution, the pole-lathe, date to around 1300 and depict women turning materials on the stained-glass windows of the Chartres Cathedral in France. While these represent some of the earliest images of the pole-lathe, there is speculation that they were around as early as the Viking age. While there is no hard evidence of its existence in Viking culture, archeological finds reveal plenty of Scandinavian wood products from the era that bear the signs of turning, as well material cores left over as waste. This, coupled with findings of other advanced tools, such as rasps, augers, and saws, make a case for its existence within Viking culture – centuries before the earliest discovered depictions in art.

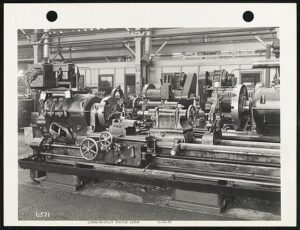

The lathe continued to see small improvements in the centuries following, with one significant overhaul – horse powered machining, during The Revolutionary War. However, all sorts of technologies were taking their first steps in a coming-of-age journey as the Industrial Revolution approached. From the spinning jenny to steam engines, the world was seeing rapid technological growth at a pace unrivaled to that point. One of the people that contributed to this growth was Henry Maudslay. An English locksmith turned ship manufacturer, Maudslay had a knack for inventing machines, and one of his greatest creations was a re-imaginging of the traditional lathe. His vision for a sliding rail system improved accuracy and precision by allowing tools to move smoothly along his device, and in 1800, he brought that vision to life. This groundbreaking development allowed him to standardize and mass produce screws, but it wasn’t long before the metal lathe became a mainstay in manufacturing for everything from train and ship parts to tools and hardware. Effective as it was, the metal lathe had still more to give. Engine lathes, metal lathes that ran on steam power, would play a keystone role in industrialization throughout the 1800’s and well into the twentieth century. Today, engine lathes are common in industry setting everywhere, though electric motors have long since replaced steam power.

If we look at the landscape of machining today, there’s a lot of hype surrounding computer numerical control (CNC). This approach to manufacturing involves merging programming technology with traditional machining tools, the result of which is equipment that can operate its own run cycles. With some clever software and the touch of a button, CNC lathes don’t require any turning by human hands at all.

CNC got its start in 1949 when John T. Parsons and Frank L. Stulen collaborated on the development of an efficient and accurate way to manufacture rotor blades for Air Force helicopters. Using punch card numerical control with an IBM 602A, they won the contract and became the progenitors of today’s modern CNC machining process. The next 40 years would see rising popularity and accessibility of numerical control technology. Complimentary inventions like CAD and CAM software would take machining processes further toward full computerization, and CNC became the standard in machining technology by 1990.

Despite advances in technology over millennia, the lathe hasn’t changed all that much. From a simple spindle and strap system powered by a pair of hands to a fully motorized computer-controlled powerhouse of modern industry, the lathe has certainly become easier to use, but its core function remains as it did in the time of the Egyptian Empire over 3000 years go. Still today, the lathe oversees our ability to shape the physical world around us and will continue to do so for a long time to come. As the world keeps turning, so too will the mother of all machine tools, the wonderful lathe.